Finding the Temple Within

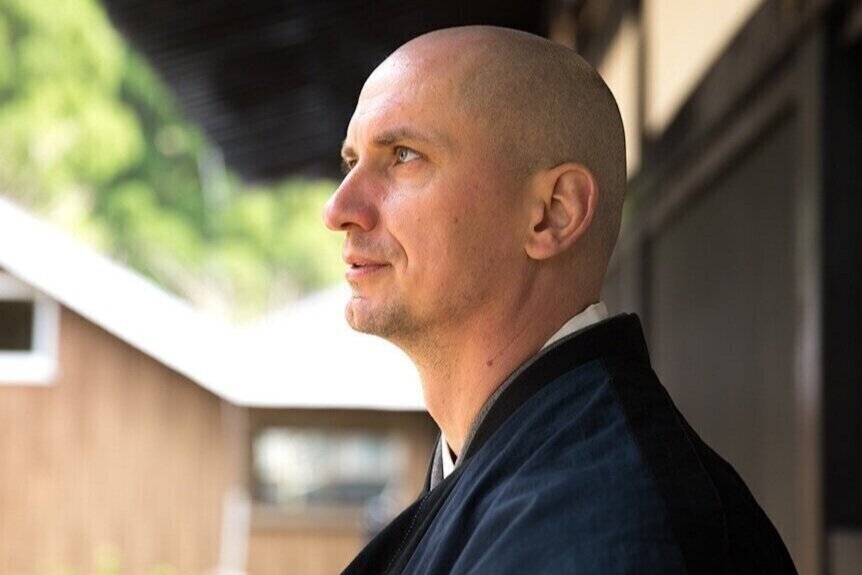

MAE Y in conversation with Muhō Nölke

Muhō Nölke is a German-born Zen monk who in 2002 became the abbot of Antaiji, a Japanese Sōtō Zen temple deep in the Hyōgo Prefecture mountains, where they farm their own foods. Born in Berlin in 1968, Muhō was introduced to zazen at age sixteen. After graduating from university, Muhō ordained as a monk under the abbot Miyaura Shinyū Rōshi. He has translated works of Dōgen and Kōdō Sawaki and has authored four books in German and several books in Japanese. Muhō has been married since 2002 and has three children.

MAE: In my book, Tsunami, Kizuki, I write about the tsunami experiences in my personal life, and what my subsequent kizukis have been—the epiphanies and unexpected insights that have opened me to a new dimension of awareness. A large theme in the book is the intimate connection between death and love—because I discovered that death is not at all what people think it to be.

What are some of the major tsunami experiences in your life, events or moments that have shaped you to become who you are today?

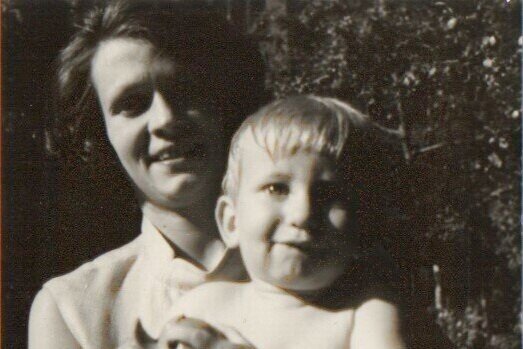

MUHŌ: The first and maybe the biggest tsunami in my life happened when I was seven years old and I lost my mother. She was thirty-seven at the time and had been diagnosed with cancer about one year earlier. So, it was a pretty sudden thing. One day, when I was playing soccer by myself, my aunt came to me and said, “I have to tell you something. Your mother’s not going to come home. She died.”

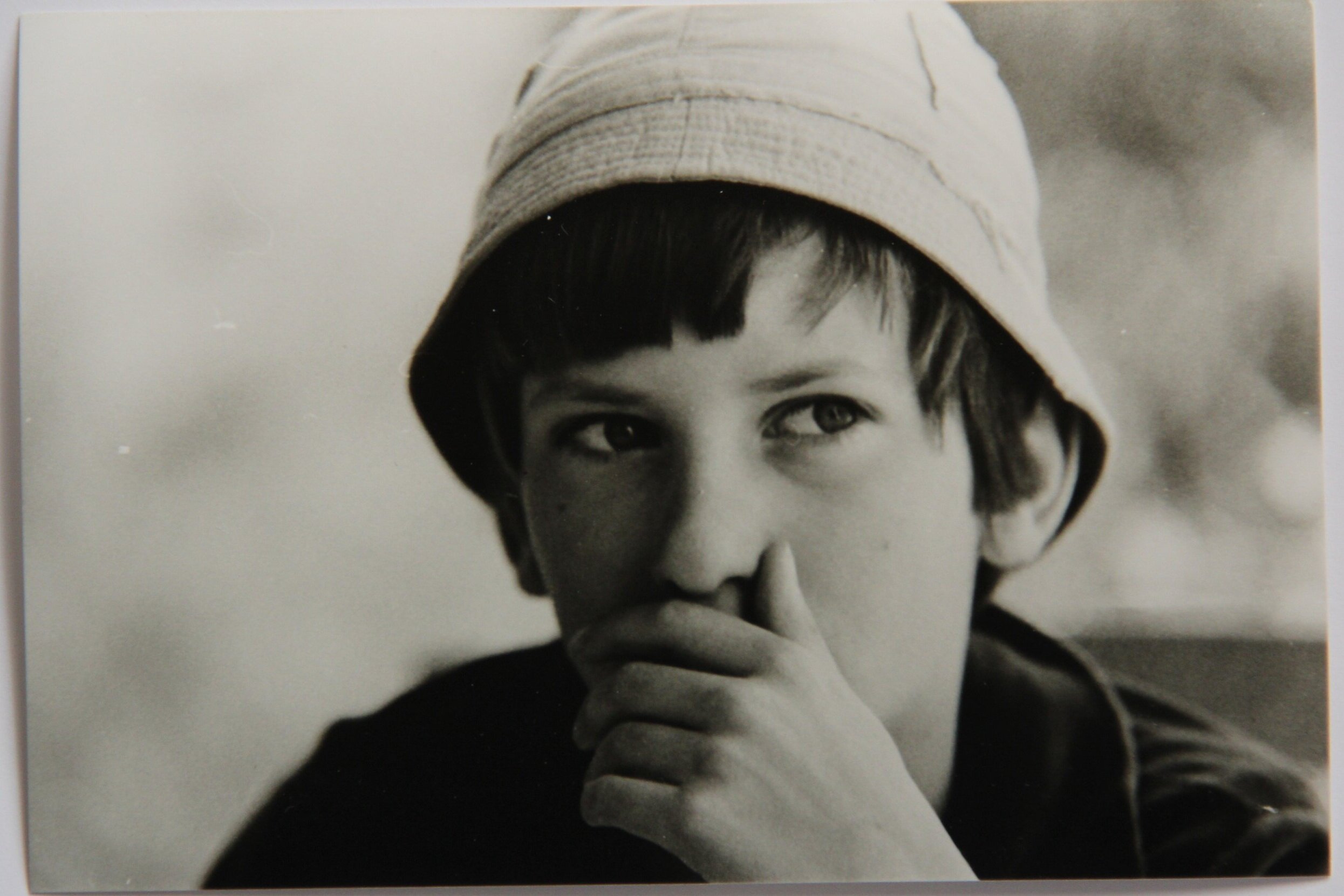

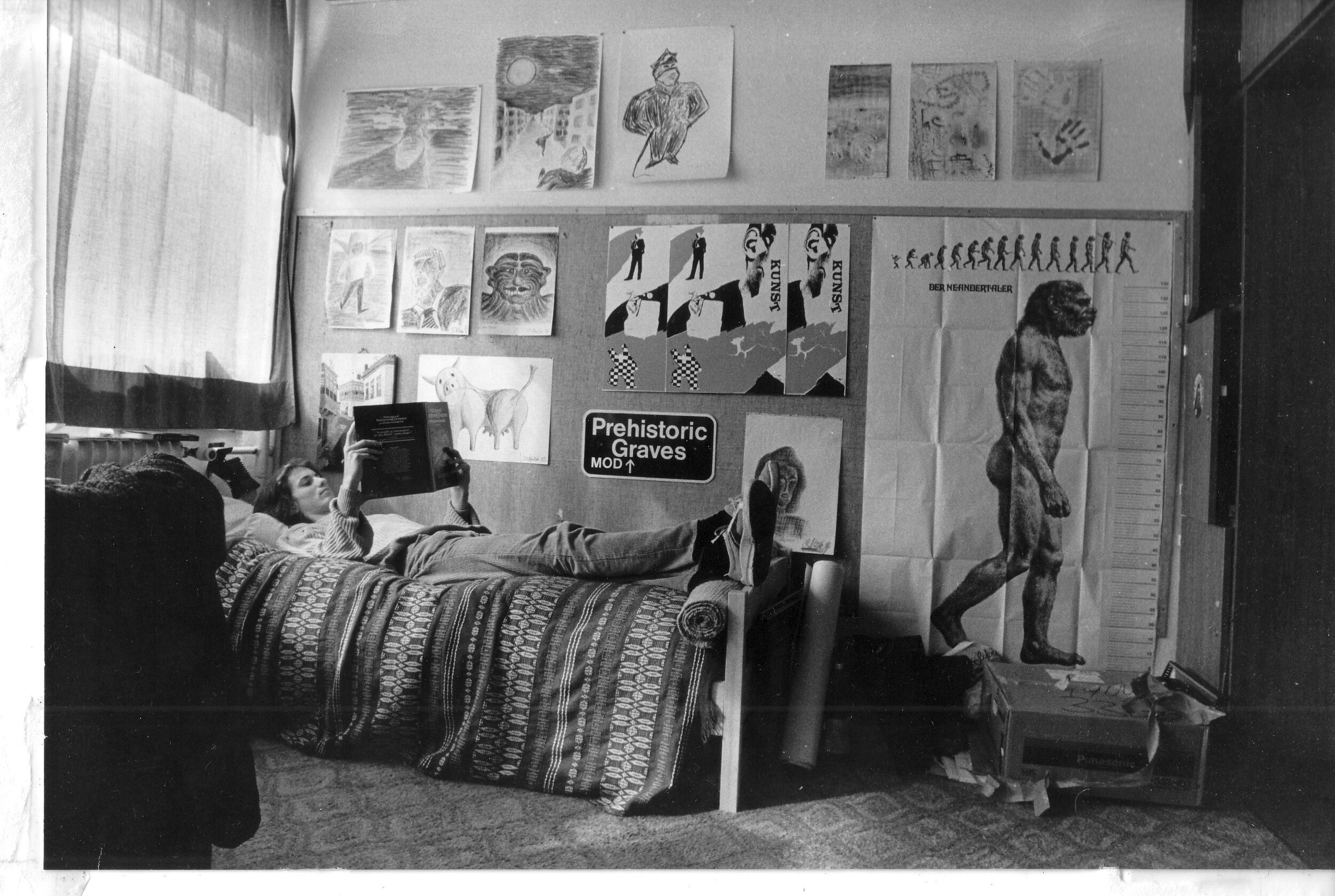

As you can imagine, that was a huge tsunami. I spent many long afternoons and weekends mostly lying on my bed in my room, looking up at the ceiling and thinking: Well, if we all die, why should I do homework? Why should I go to school tomorrow? I voiced these questions to some people, and they would tell me, “If you don’t study, you can’t go to a good high school or university.”

“But why do I have to do that?”

“Well, to get a job.”

But when I looked at my father leaving for work every morning, he didn’t look so happy. When I asked him, “Why do I have to study to get a job and go to work?,” he said, “To earn money, of course. Without money, I can’t provide for all of you.”

But my real question was: You’re going to die, I’m going to die, everybody’s going to die. So why do we go through all of this?

My father suggested that I ask my teachers at school, and at school I am told it’s too early for questions like that. “You have to wait until you are in high school.” But in high school, still, nobody teaches you. Already at age seven I had the feeling that the grown-ups didn’t know the answer to my essential question: Why do we live?

MY: During the year of illness, did your mother know that she might not recover, and did your father have an idea to prepare you and your sisters?

MN: I think they were trying to figure out how to cope with it themselves. My mother was working as a doctor, and her life was divided between home and her job at the hospital. My father was also working. And then there was this sudden announcement—“You have cancer.” That must have been a big shock for her.

I was later frustrated because when my mother died I was 600km away on summer holidays at my aunt’s house. I asked if I could attend the funeral and they said, “No. You are only seven years old; it’s too early for you. A little kid has nothing to do at the funeral.” That was something that I never really forgave the grown-ups for.

MY: Even now?

MN: I don’t harbor any bad feelings because of that now. However, in Japan it would be unthinkable to not allow a child to be at their mother’s funeral. The fact that I was told: “You’re still a little kid, you don’t understand,” frustrated me because the adults couldn’t admit that they actually didn’t know anything either. They tried to create a façade of normalcy.

MY: They didn’t know how to deal with it.

MN: Yes, which I can understand. If I, at that age, were told, “You’re going to die,” or, “Your wife is going to die,” I don’t know with certainty what I would tell my kids. But at the time, I wished that they would’ve at least been able to say, “Honestly, we don’t actually know what to tell you.”

MY: Yeah, as a child, when grown-ups treat you that way, unknowingly, it’s like they don’t treat you like you’re human. It’s like there’s a belief that just because you’re a kid, you don’t need to know. Glossing over the truth never really works.

MN: Yes.

MY: Did you have any other person you could go to, like a therapist or any other adult you could talk to about your true feelings? Or did you feel really alone?

MN: I felt alone. In Germany, school typically ends at lunch time, and you return home in the afternoon. So, I usually spent the afternoons by myself, reading books.

There was no therapist. I think relatives may have told my father that I might need support. My name when I was younger was Olaf, and so they said, “You should send Olaf to a therapist.” But that didn’t happen.

So the question persisted: Why live? I was never really seriously suicidal, but there was always this thought in my head: Why would I live until the age of eighty when I can die today? That would make things so much easier. All this suffering, all this boredom. All these long weekends would end if I would just kill myself. But it was never so urgent that I felt I needed to do it “today.”

MY: It’s fruitless to try to measure suffering, like how much sadness; how much depression; or how much grief, you know? It’s so subjective that there is no comparison. But for some people, it’s too much; they actually go out and take these actions. For others, like for you, it seems that something was anchoring you. Even at such a young age, and even with so little adult guidance, it sounds like you had an innate wisdom or knowing. You had this huge question: Why live? You were hit with life’s suffering and wondered, why go through it? Yet, you were not a quitter.

Have you ever thought about what that anchor was or is?

MN: My main question at the time was, as you just said, Why live? If I’m gonna die, if everybody’s gonna die, why live? But then, after a while, there was a second question, which was: Who is asking this question?

MY: Wow. That is so powerful. How old were you when this question emerged?

MN : I don’t know exactly. It could have been when I was nine or ten. But I know there was this thought: I’m thinking here, but who is it that thinks, “I think”? Who says, “I need to know why to live.”?

MY: Wow.

MN: I never really thought until you now asked me that this realization might have been the anchor. Maybe it was this realization that there’s something behind the question that was the kizuki.

MY: I am curious about this on many levels. As I have gone through my grieving process, I’ve also held my son Issa through his grief and recovery. You can’t even take turns—you have to grieve simultaneously. It’s been a lot.

In your case, you were so isolated. Did the presence of “mother” come to a full stop at death? Or did you feel her presence, in a more spiritual sense?

MN: Not so much.

MY: Was your family religious at all?

MN: My grandfather on my mother’s side was a minister. But he wasn’t really a typical religious minister. He was also a socialist. He stressed that we are all brothers and have to cooperate. This was the late 60s and into the 70s, and for him it probably felt old-fashioned to talk about the relationship with God. It was more about humanity for him. And so, although I grew up in the minister’s house until I was six, I wouldn’t call it a religious environment.

When people would say, “Love thy neighbor,” I was full of doubt. Okay, yes, I understand that I should love my neighbor just like myself—but HOW can I love myself?

MY: That’s a big one.

MN: That was my problem as a kid. Even when my mother was still alive, because she was working long hours, I always had this feeling: I don’t have enough love from my mother. As with most people who are first-born children, at first you get a lot of attention, but then there’s a sister or brother. All of the sudden, you’re only one out of two or more. You’re told, “You’re a big brother now, you can tie your own shoes.” So even when my mother was still alive, there was still this feeling: I’m missing . . . I’m missing . . .

MY: Did you play with your imagination? Did you have imaginary creatures or friends to comfort you?

MN: No. In church, I heard about God: “God is always there; God is watching you.” It never really made much sense to me.

MY: Even before your mom died, it didn’t make sense to you? You never bought into it?

MN: No, no. In Germany, when the Christmas Santa Claus comes, he has this big bag of presents in one hand, and in the other hand he has a paddle to beat little kids’ behinds. He will only give presents to the good kids.

MY: Wow! I didn’t know that.

MN: Yes, he’s kind of playing the role of the oni (ogre) in Japanese. He can be the very kind Santa, but if you don’t behave, he’s going to be the oni for you.

I remember one Christmas when I was six and Santa asked me, “Have you been a good kid this year, Olaf?” I wasn’t so sure, so I said, “Yes?”[questionably.] Santa looked at my mother and asked, “Is that really true, Mother?” And my mother said, “Mmm . . . I think he can still improve, but as it’s Christmas today, Santa, let’s give him a present anyway.” Then I looked back at Santa and I realized: That’s not Santa! That’s my Uncle Peter! All of that was a made-up story! Every kid at some point has this realization, that it was all some made up story.

Since that time, I couldn’t believe the stories in church anymore. Stories like: You’re a sinner. You don’t believe in God, and you’re going to go to hell. If you behave, and if you believe in Jesus, you’re going to go to heaven. Where is the difference between those stories and the story of Santa? Aren’t they made up as well?

MY: I’m so impressed by the sharpness of your mind. Especially because it sounds like you didn’t have such an example as you were growing up. Even to question Christianity, to question Santa, to question death, or to question belief, you’re already recognizing that belief is a choice—you had that kizuki. When you stepped out of that mindset, you made the connections: Oh, if you go to church, all of these people are buying into that belief system. If you go near Santa, all the kids are buying into that belief system. But it’s actually my uncle.

There is that self that is outside belief, a greater consciousness that can step aside from it—even though, of course, as a child, you weren’t yet aware of the awareness.

It sounds to me that at every corner you were so guided that way, you know? Dare I say, you’re so blessed that way. Because that’s such a sharp level of clarity at such a young age. And that is such a tremendous gift.

So how did you cope with the pain? Because you were so alone and you were still such a young child?

MN: We’re talking about the time before the internet and before there were computer games. But I loved to solve riddles and mathematical riddles that were usually well above my age-level. I also loved to spend time in my thoughts. Later, there were role-playing games, like Dungeons and Dragons. I had fun in this imaginary world where I knew the rules, or with mathematics, where I could solve problems. In the games I felt safe. And at least for a time, that would get my mind off of the question, What is life in the first place?

MY: Yeah, like it all makes sense.

MN: Yes. It makes sense.

MY: In your late teens you discovered Buddhism. Can you tell us about that?

MN: Well, that was the first kind of kizuki that went a little bit deeper.

I was sixteen and had entered a Christian boarding school. There happened to be a teacher who was into Zen meditation, and he asked all of the students if they were interested. At first, I said no because I didn’t feel really interested.

There was a famous Indian guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Later he used the Japanese word “Osho” to refer to himself. In the 80s, Osho was all over the media in Germany, but not in a positive sense. There was a food poisoning incident in America that was connected to some of his devotees. Then there were all of the Rolls-Royces. He had close to one-hundred of them. And then there were the transcendental meditation guys who were claiming they could levitate. Basically, I had heard all of these rumors about meditation and spiritual communities and it all sounded a little bit strange to me.

So, when I was invited to a Zen sitting, in 1984 when I was sixteen, I was dubious. I said, “No way.” After two or three weeks, there were not enough people coming to the meditations, and so the teacher came around a second time. I was even more suspicious. But then he asked, “Have you tried meditation? Without trying it at least once, how can you say it doesn’t interest you?”

I couldn’t argue against that. And even if he were to attempt to brainwash me, he couldn’t succeed in one try. I’m gonna go there once, and then I’m gonna tell them, it’s not for me. So, I went and . . . well, he obviously succeeded in brainwashing me! (Laughs out loud.)

MY: (Laughs.) Look at you, you’re in Japan now, a monk for thirty years.

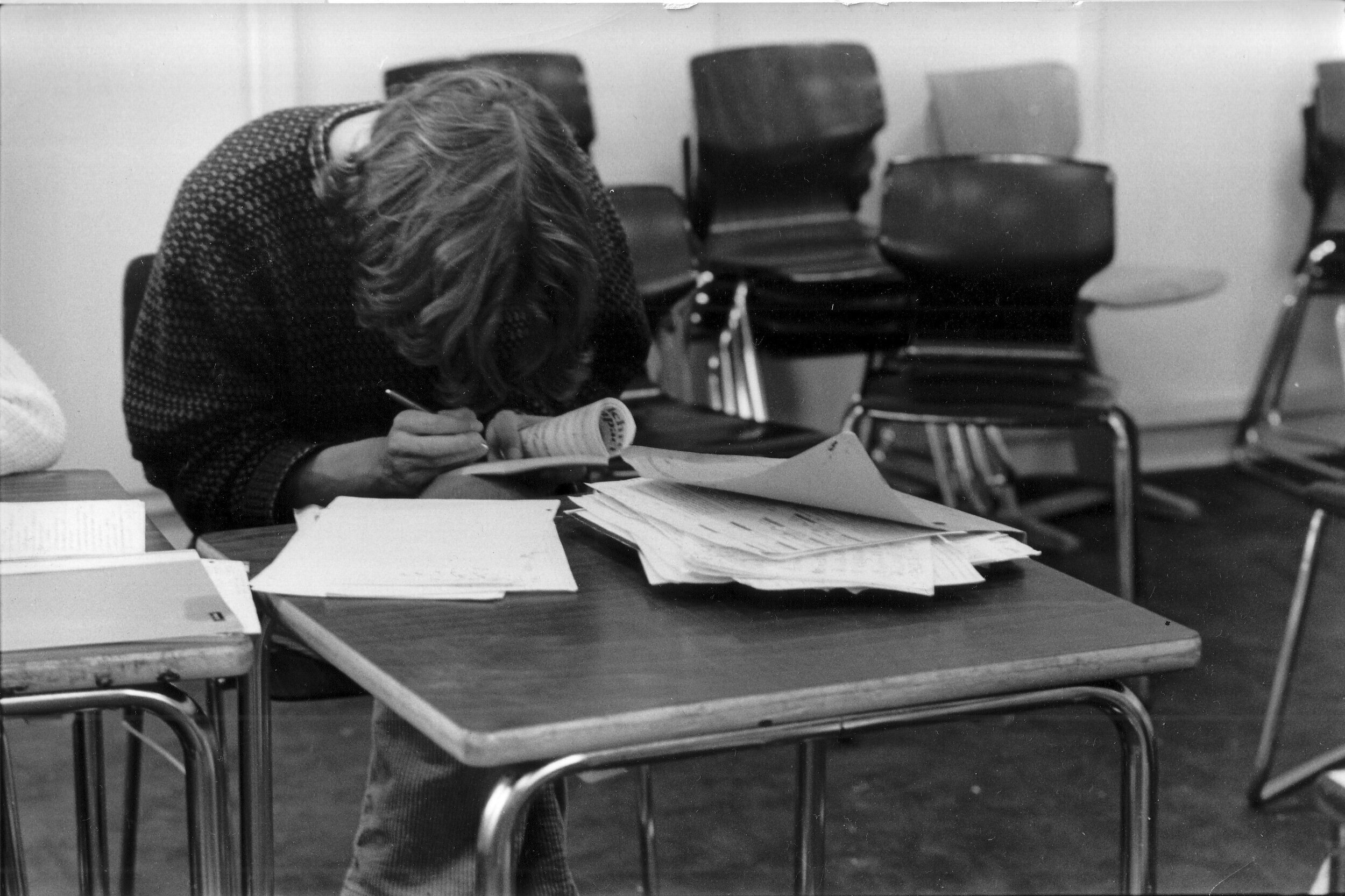

MN: When I was in school in Germany, I was usually sitting like Rodin’s Thinker or leaning back in my chair. Teachers there are not so strict about the posture; it’s basically up to you. So one of my first kizukis, a big surprise, was, How I sit matters. If I lean back or sit in lotus posture or sit in what we would say in Japanese is the agura [cross-legged] posture, it matters. Sitting straight in meditation was one of my first WOW experiences. I could sense, something is different here.

The meditation started with following your breath. When you breathe out, breathe in. This too, was a surprise. I had been thinking so much about life and who I am. How come I never paid attention to my breath? Outside of the window there is rain that starts to fall. Lots of small things that I never paid attention to. There was this realization, this kizuki: How come I never saw the world? That was another one of the first big kizukis that brought me back the next day and the day after that, and basically for one year I was always sitting there.

After the meditation, the teacher would ask all of us, “What did you experience?” Almost all of the participants had a story to tell. One person said, “I saw myself walking over a big meadow of flowers and it was really beautiful.” And another person said she saw a golden pendulum swinging inside herself. But I always had to say, “Sorry, there’s nothing happened yet. But I would like to come back tomorrow.”

After one year, the teacher left the school, and to my surprise, he asked me to continue with this group as the person responsible for organizing the meditation. That’s when I started to read books. I felt that I needed to study the theory behind Zen meditation. I started by reading D.T. Suzuki, who was already well-known in the West. And then I began to read Indian Pali sutras. I read for the first time about Shakyamuni, the Indian prince, who said, “I’m not going to become king. Because I don’t know why I’m born, I’m going to get old, I’m going to get sick, I’m going to die. Nothing in life is actually the way I would wish it to be.” He was saying that life is suffering. Non-satisfactory. “Why is that and what can I do about it?”

When I read that, for the first time in my life, I felt that I had met my soulmate, so to speak. Wow! I was not the only one. There was somebody before me. And it’s a whole tradition.

That was the point where I decided, after high school I am going to go to Japan and become a monk. Not only does it feel good to sit there, but obviously somebody has found the answer to the question I always had. And, hopefully, this is going to get me there—to the answer I’ve been seeking.

I was seventeen, with hair that was growing well below my shoulders. Then for the first time I shaved my head.

MY: Normally when people sit for the first time, whether they’re sixty or sixteen, they get very fidgety. They get antsy. They start thinking about things. Either they fall asleep, or they want to move around. There is such a strong, powerful existential force inside you, where you sit there and say, “No, I didn’t see anything like my friends did. I didn’t hear anything like my friends claim to have; it was nothing for me.” And yet you keep wanting to come back . . . to nothing.

Was there a point when you had a thought like, In order to recognize “nothing,” I must have had awareness?

MN: Mmm . . . I never thought about it that way. In order to recognize nothingness, there needs to be awareness . . .

I was always an introvert. So this kind of internal perspective was nothing new for me. In zazen, one thing I enjoyed was that it was okay to be just there. You don’t look around, you don’t have to talk; you don’t have to do anything.

For many people, it’s a major spiritual realization to discover that, actually, I am not my body. Until then, they identify strongly with the body. But then they realize something beyond.

For me it was the opposite. I was always attached to this beyond. Why live in the first place, why am I stuck in this body? Why do I have to live this Olaf? But Zen connected me to the body. There’s this body that is also you. And changing the body changes everything. It changes the world. Of course, then, to be awareness at the same time.

MY: And where would your emotions play a role in that?

MN: My emotions . . .

MY: Sometimes when we sit in meditation, emotions and memories come up. Especially when there’s been memory of trauma. Some people have them visually and vividly. Other people have them in more sensational ways. In your own experience within, what kind of role do emotions and memories play?

MN: In Zen, as I studied it, there was never any kind of methodological approach that would say, if an emotion appears, let’s deal with it in this way or that way. Rather, you’re told to let everything go. To accept, but also let go. Accepting and letting go are two sides of the same thing. Letting go doesn’t mean that you push it away. You accept it as it is, and at the same time you don’t cling to it. You let it go.

That of course is very difficult. When I did my first sesshin [period of intensive meditation in a Zen monastery] at seventeen or eighteen, I sat from morning until night for five days, and a lot of stuff came up.

MY: Yeah, the stuff. The stuff.

MN: Yeah. The pain. And the: Why am I doing this? I could have fun with my friends now, I could try to find a girlfriend. Why would I sit and look at the wall for hours and hours and hours—and for several days? And you start to hate yourself, and you hate your neighbor who’s moving around and making noise; and you start to feel hungry. And then there’s ruminating over all the conversations you’ve had in the last couple of days or weeks. There’s anger and greed. And also stuff that you thought you had long forgotten. Sometimes you’re surprised that you’re still carrying all of that around.

There were times where I started to cry during zazen. But it’s not a group session. It’s not that somebody comes over, touches your shoulder and says, “Hey, let’s talk about this. How can I help you?” I came to understand it as kind of an internal digestion process. You start to digest all this stuff you’ve been carrying—all this mental constipation. For a long time, you didn’t even realize it. When people sit, often they have this realization, and they’re almost shocked or disappointed. They think they’re going to sit, and they’re going to relax and be peaceful. But often the opposite happens.

MY: When you talk about this mental noise, I think most people want to ask, “Okay, so what do you do with it?” But you’re saying, all that stuff, that’s just constipation, that’s just clogged up stuff. It’s normal. In Zen, you sit anyway. All the emotions, the thoughts, they are what they are, and you just sit anyway.

It sounds like the sitting itself is the method that helps to just release the flow. So, the emotions come, the thoughts come, the chaos comes. The trauma comes, the memories come. But then you release.

And of course, there is the realization that it always passes. There’s never a thought, there’s never an emotion that stays. It always comes, it always goes.

But right there is one of the big misconceptions of the larger world, where people think that the solution is to think through it. So if you have anger, for example, often people think that they’re supposed to take some sort of action. Should I express my anger? If I meditate and it comes up, do I need to leave the room? Do I need to go and see the person who’s triggering the anger and talk to this person? People end up engaging in the thought and then actually creating more constipation around it, right?

MN: Yes, yes.

MY: But it’s such a HUGE realization to know. I mean, you make it sound so easy when you say, “Oh, yeah, you just sit anyway.” I’ve been to your temple. I’ve done half a day of sesshin, so I have an idea of how that goes . . . and yes, you sit anyway. But for most people to come to that realization, it can take years.

MN: Yes.

MY: For me, in my personal experience, when I started yoga at twenty-one, I learned that my physical ailments came from my mind. After yoga practice, my teacher would have us sit in agura and we would meditate. Afterwards, like your teacher in Germany, he would ask us, “Does anybody want to share?” There were students in the class who would say things like, “Oh, there was a field of lavender and it was vibrant purple and it smelled so nice.” And I always thought, Are they kidding? We’d just closed our eyes. That’s just your imagination. I’m not seeing anything! You know?

The only instruction my teacher ever gave us consisted of two words: “Just observe.” Just observe. Now, almost twenty years later, I still come back to those words. Just yesterday I was thinking to myself, Those were the best instructions I ever got in my entire life.

I could go off on a two-hour lecture at my studio about why we should just observe, but again, that just engages everyone’s thoughts. It’s entertaining. But really, the practice is just to observe. And that’s enough. But it can take a long time to get there.

if you don’t become a buddha,

there is no buddha.

~Muhō Nölke

MY: Let’s talk about the temple master at Antaiji, the Buddhist temple, who was one of the key teachers in your life before you became the jushoku (temple master, abbot). What are the lessons that you picked up from his influence?

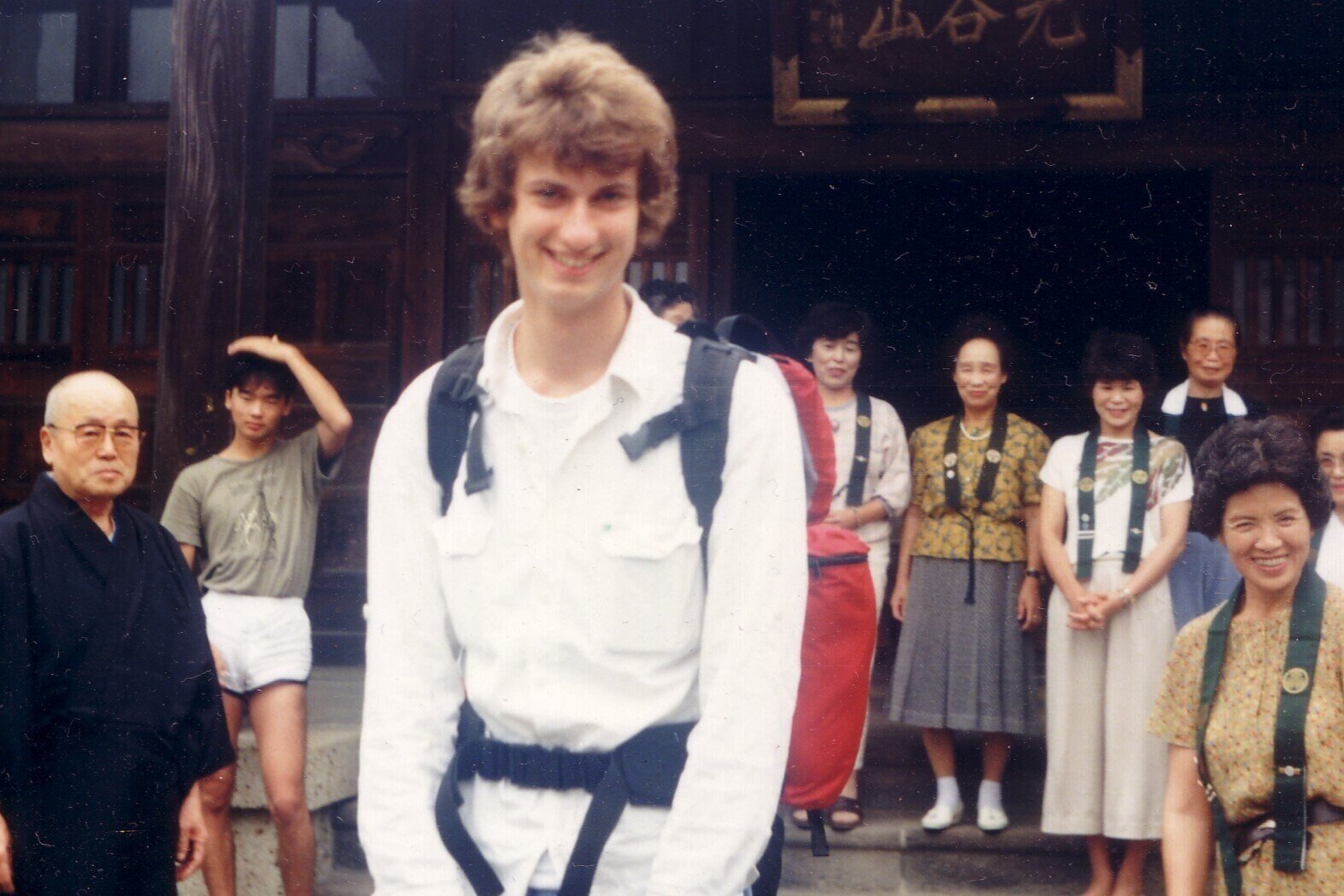

MN: When I was twenty-two, I had come to Japan for one year as an exchange student. The original idea was to spend that year in Kyoto, but then I heard about Antaiji, where I could sit and meditate, so I decided I would spend the remaining months in Antaiji before going back to Germany. When I arrived there, the abbot—who would later become my teacher—asked me, “Why have you come to Antaiji?” I said, “I have come to Antaiji to learn something about Buddhism.” And he said, “This is not a school. We are not a school. You create Antaiji.” This took me by surprise, of course. I was only twenty-two. I thought, How can I create anything? I’ve come here to study.

“You create Antaiji.” That’s something that stuck with me for a long time. It was my first big lesson.

I went back to Germany and earned my masters in Japanese when I was twenty-five. Then I returned to Antaiji to ordain as a monk. I had grown up in a monotheistic environment, so at first I had doubt arise: Why does Buddhism include so many tathagatas and bodhisattvas? I thought it is only Shyakamuni, the Buddha? How come there’s also Amitabha, Vairocana, Avalokiteshvara, Manjusri? Even in front of the toilet there was an Indian deity who is responsible for the toilet.

I asked my teacher, “Who is the real Buddha? Who is that one Buddha in Antaiji?,” and he said, “Who cares? If you don’t become a Buddha, there is no Buddha.”

These two teachings made an impression on me in those early days: You create Antaiji. And, If you don’t become a Buddha, there is no Buddha.

MY: I know you would sit in extreme states of solitude for extended periods of time with ascetic practices. Have you had any, what you might call, mystical experiences?

MN: Of course, there are lots of things that happen during this digestion process. At a certain point, you hit a wall and the wall doesn’t let you get through it. I mean, you reach your limit. It’s both the physical limit, the pain in the legs and back, but it’s also mental. This is killing me. This is really killing me. Especially during sesshin.

There was always the thought: You can go back to Germany. Maybe I could go back to university or try to find a job, start a family, whatever. But I didn’t feel ready for that either. I felt I had no alternative than to stay here, no matter how hard the work in the fields was or how hard the sesshins were.

There was one sesshin where on the third day I hit a wall. I felt like, I’m gonna die. But I don’t wanna go back to Germany like this. I asked my teacher about this. “Each sesshin, there is this thought that it is going to kill me. What shall I do?”

And he said, “Why? I don’t even understand what the problem is. We have a graveyard just behind the meditation halls.”

MY: (Laughs out loud.)

MN: “If you die, I’m going take care of your funeral. Don’t worry,” he said.

Whenever I tell this story, of course, everybody laughs. And I would’ve liked to laugh too, at the time. But the next month again, it was a real problem. “This is killing me!” And the only thing my teacher said was, “Well, don’t worry, there’s a graveyard waiting for you.”

At a certain point I realized that I didn’t want to escape anymore. That wasn’t going solve the problem. Plus, I didn’t want to go back to Germany. So, I would try, knowing that the worst case scenario would be dying here in Antaiji. If I were to die during Zen practice, why not? I mean, it’s a beautiful place to die. It’s a beautiful place to have a grave. And my teacher told me he would take care of the funeral. That would be an honor. A real honor.

So, once I decided to sit still and accept, even if it felt like it was killing me, the next moment everything was easier.

I realized that I was causing this pain, this fear; this feeling that somehow I must fight through this, I need to digest this constipation. No, no. You let it go through. And once you stop and accept even death, if it should come, then everything changes. That moment, for me, was the first moment I realized that I was living.

That was, for me, a big liberating experience. It’s not that all of the pain dissolved in the moment, but I realized, it’s only pain.

MY: I also wrote a lot about this in my book. The word that I use is resistance. There’s pain, and you go, “Oooh, it’s pain—pain—PAIN.” You freak out over it. But it’s a lot of resistance, and however much you need until you come to the realization that, Okay, I can’t fight this any longer. Then the only thing left to do is to release. To let go. To just let it be. To just accept it as it is. And then, for the first time, you turn the page, beyond the pain, and beyond the resistance. What you are left with is what is, just as it is. Except now, you’re okay with it. Or maybe even better than okay. You’re so liberated because you are without the idea of how things should be. How life should be. How your mind should be. How your emotions should be. All just is.

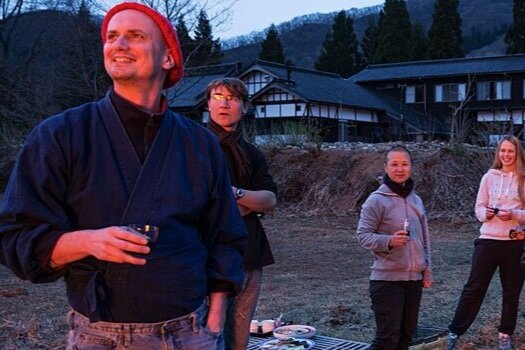

MY: If I’m not mistaken, you’ve spent thirty years in Antaiji, in the mountains, and recently you decided to leave.

MN: Yes, it’s been about twenty-seven years, and in the autumn of 2018, we decided it would be time to leave. My family moved here [to Osaka] last spring.

MY: This is a huge decision for you to leave this temple where you have spent so much of your life! You lived and breathed and worked, and you really did create Antaiji for the thirty years that you spent there.

Once you leave the physical presence of Antaiji, you’ll carry it with you inside. What does your Antaiji within look like for you now? Do you have any ideas about what life looks like for you in 2020 and beyond?

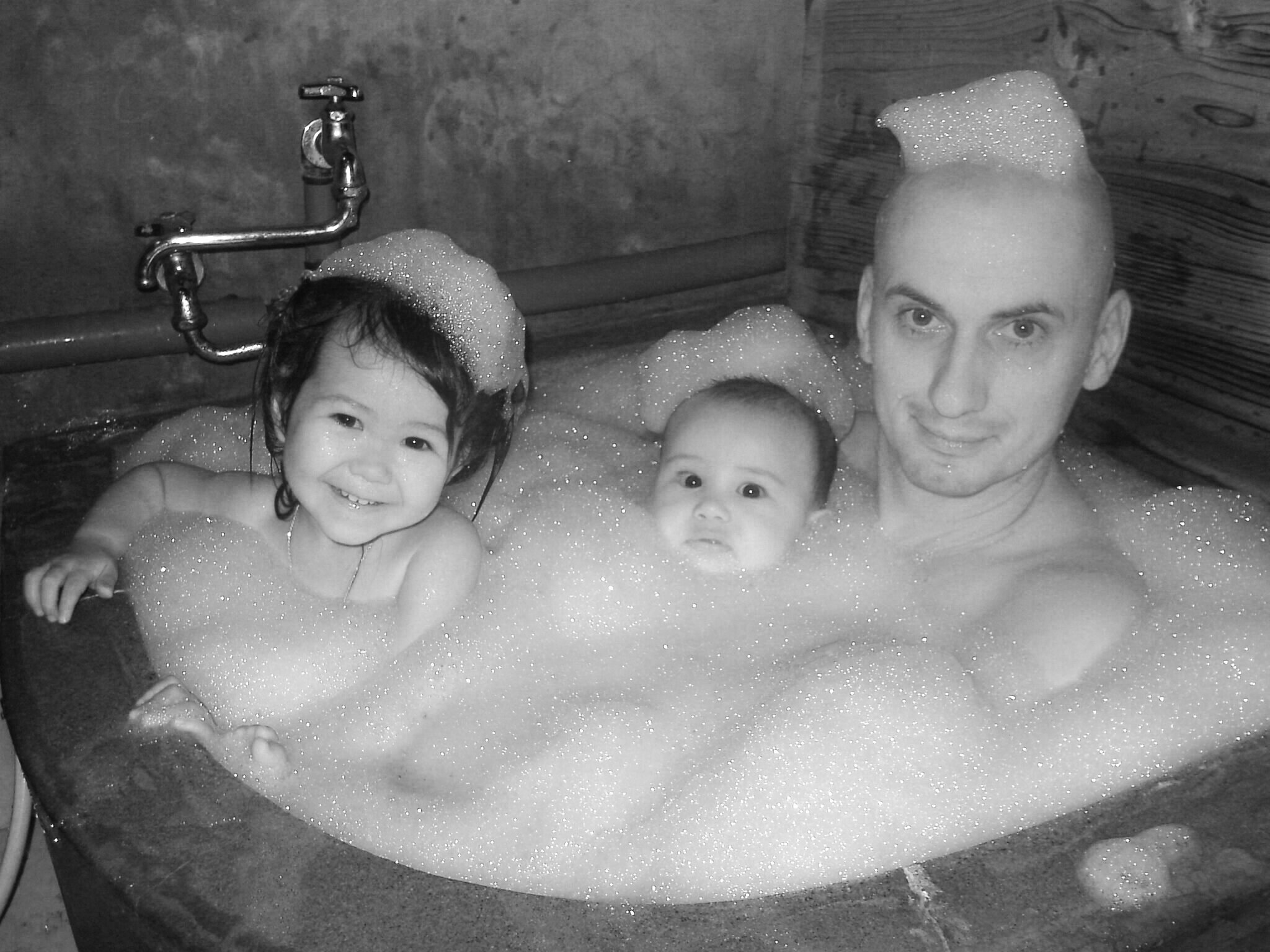

MN: Although I owe a lot to Antaiji, I spent more than half of my life there, it is also still a great liberation . . . to leave the physical place. I mean, it’s a lot of responsibility. People looking for the answer to their questions, just as I did. I often had the feeling that I couldn’t really give enough to everyone, and, at the same time, be a responsible father in the family and be a good husband for my wife. Recently I’ve been writing books and giving a lot of talks, and I enjoy that as well.

With my personal Antaiji established within me, I can decide, for example, how much zazen I want to do. Right now, I do it on Sundays in the park and invite people to join me. But I don’t have to sit there every morning at 4:00 AM as was the case in Antaiji. I enjoy the freedom that I have now. I have more time to share with my kids, more time to be with my wife. I have more time for myself. I started to practice yoga, together with my wife. I enjoy being able to do things like that, which I just didn’t have the time for when I was doing five hours of sitting meditation on average per day.

MY: Yeah, I’ve been to Antaiji, I understand. Not having to work in the fields and run your tractor and wake up at 3:30 AM and wash your hands in the water that’s so freaking cold in the wintertime . . . and the bells that you ring! I mean, they’re not even nice bells, like ding-ding. They sound more like, GZAEGZZZZZZZZZZEEEEGNGNGNGNGNGNGNGNG!!!!

MN: (Laughs out loud.)

MY: I would love to discuss specific topics further with you; for example, the relationship between Buddhism and suffering, and Buddhism and forgiveness. Until then, thank you so much. I really, really enjoyed this and look forward to doing it again. Arigato gozaimasu.

MN: Thank you. Arigato gozaimasu.